Dogtown Commons was one of Gloucester’s first settlements. In the middle of Cape Ann, with the rise of maritime trades after the Revolutionary War, the Commons was abandoned becoming the place we now call Dogtown. Other than a few artifacts recovered by amateur archaeologists and would-be treasure hunters, the old roads, stone walls, and cellar holes of Dogtown are all that remain of one of the earliest chapters in Gloucester’s history. This article is the second of three that discuss what happened to three homes dating back to the original settlement that were important places in the history and literature of Dogtown.

Just past a metal gate on Dogtown Road, a stone with a “9” inscribed on it marks the location of the Clark cellar.

In the June 1874 issue of Atlantic Monthly, Gloucester poet Hiram Rich published a poem commemorating the heroism of a person that Rich thought was Morgan Stanwood who was killed fighting the British in the Battle of Gloucester, a key battle in the Revolutionary War. The setting of the poem was Stanwood’s home but as it turned out, Rich was confused on two points – the hero was Peter Lurvey, not Morgan Stanwood, and the house was not Morgan Stanwood’s (cellar #28 on Common Road) or even Peter Lurvey’s (cellar #25 on Wharf Road) but Joseph Clark’s.

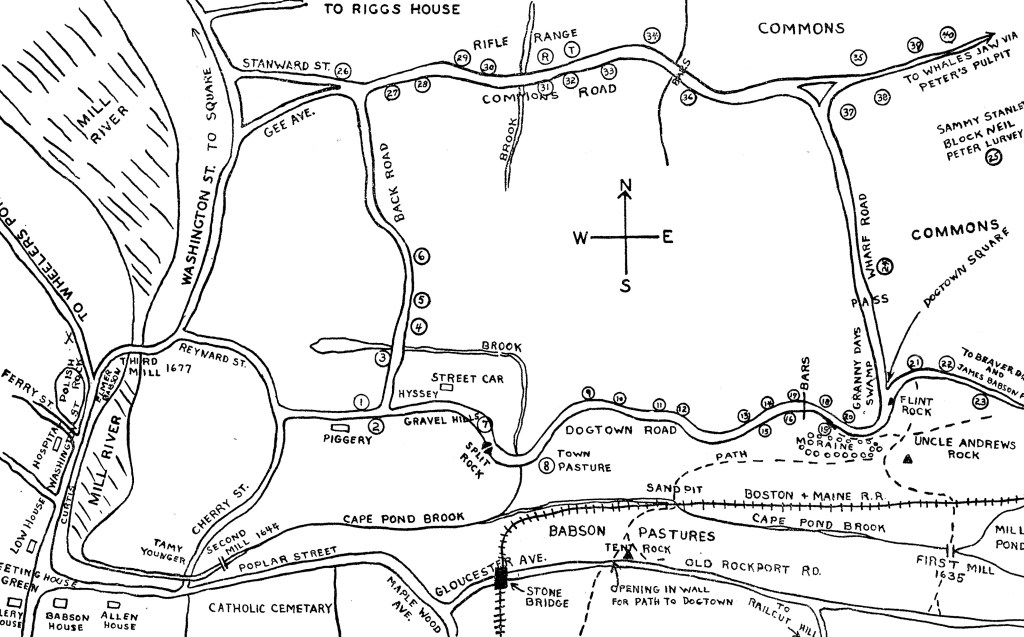

Roger W. Babson’s 1927 map from a booklet Dogtown, Gloucester’s Deserted Village later published with Foster H. Saville in the Cape Ann Tourist’s Guide.

Despite the confusion, Rich’s poem is rich in imagery. This poignant stanza describes the tolling of the bell calling Gloucester’s volunteers to action:

Larum bell and rolling drum

Answer sea-borne guns;

Larum bell and rolling drum

Summon Freedom’s sons!

Those of us who live in Riverdale on this side of Dogtown can hear much of what happens in Gloucester – from train whistles, to foghorns, to gunshots from the Cape Ann Sportsman’s Club, and other sounds that reverberate across the middle of the Cape. It is easy to close one’s eyes and picture this moment back in 1775.

Equally powerful is the imagery of a household interrupted in late summer just before harvest:

Fallen scythe and aftermath

Lie forgotten now;

Winter need may come and find

But a barren mow.

This part of Dogtown was pastureland (see Tingley’s map at the top of the article). Sheep were raised here. There were haystacks everywhere. The repeated references to the doorstep in this stanza:

Morgan Stanwood, patriot!

Little more is known;

Nothing of his home is left

But the door-step stone.

and here

Morgan Stanwood’s roof is gone;

Here the door-step lies;

One may stand thereon and think,—

For the thought will rise,—

Were we where the meadow was,

Mowing grass alone,

Would we go the way he went,

From this very stone?

refer to the house’s foundation that Roger Babson notes in his Cape Ann Tourist’s Guide “This cellar is in the best condition of any in Dogtown and here may be seen the door stone (which has tumbled into the north side of the cellar) immortalized by Hiram Rich…”

The doorstep – a flat stone with the number “9” on it is all that is left of the Clark cellar.

A Disturbing Trend

After it was abandoned in the mid-1800s and became a municipal property, with the exception of its two reservoirs and surrounding watersheds, Dogtown was left largely unmanaged by the City of Gloucester, a policy of benign neglect. Many people believe that Dogtown should continue to be left alone – to exist in a natural state. But as we have seen, two cellars were destroyed because the dirt and rocks on which they were built were more important than the history they represented. Up until a few years ago, the back of the Clark site, where the hill was, had been used by the City to dump large trees and stumps. In 2016 it was cleaned up by volunteers.

Located just past the gate, the Clark doorstep overlooks Gloucester’s compost area – an ugly scene that is in stark contrast to the inspiring imagery of Rich’s poem.

An inventory of Dogtown’s archaeological resources identified dozens of sites of historical importance. Given the City’s past performance in allowing the Clark and Stanwood cellars to be destroyed, can they be entrusted with protecting scores of other unique places in the future?

The next article discusses another lost site that could still be saved.

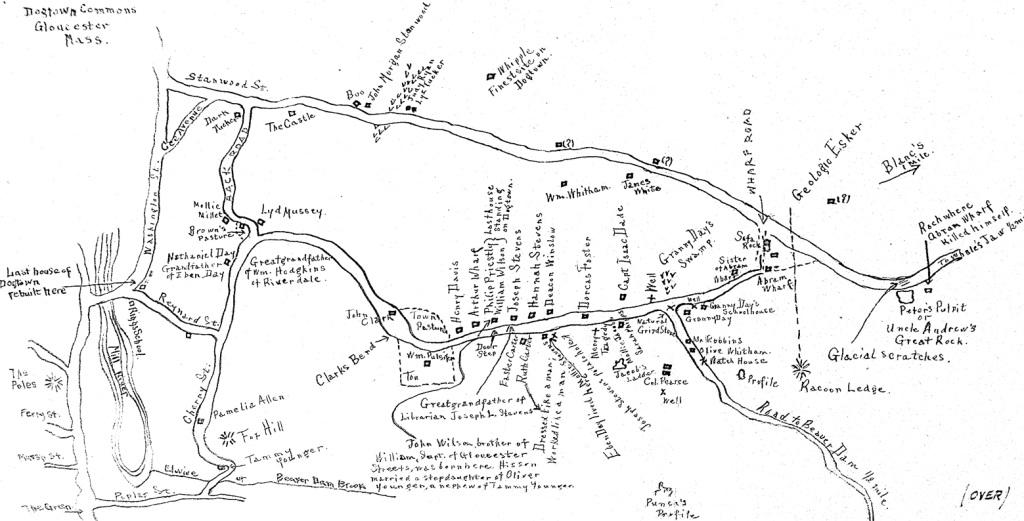

The map at the top of the article was drawn by X. D. Tingley, a Gloucester public school teacher in the late 1800s (Courtesy Annisquam Museum/Mary Ellen Lepionka).

Leave a comment