It seems that every generation has considered the question of what should be done (if anything) about Dogtown. And each has reached an impasse of one sort or another. Although the situation is considerably better than it was in the late 1950s, there remain key parcels, that if developed, would destroy important historical sites and split Dogtown in two. The article reviews land acquisitions over the past sixty years that have led to the current situation in which Dogtown as a whole is neither threatened nor protected.

The Dogtown Foundation

In August 1958, a group known as the Dogtown Foundation published a statement of its plans to preserve, restore, and protect a proposed 670-acre reservation within Dogtown. In June of the following year, the Gloucester City Council approved a request to the State Legislature that a bill be passed authorizing the City to take, by eminent domain, land for a Dogtown Reservation and lease it to the Dogtown Foundation for a term not to exceed fifty years. Under the agreement, once the City had acquired the land, the Dogtown Foundation would manage the land, covering the cost of upkeep and maintenance through donations.

In the 1950s more land in Dogtown was privately owned than it is today. In a June 27, 1958 letter to the Gloucester Daily Times (GDT), H. Lawrence Jodrey of Rockport writes: “When an area is sparsely settled, people … enjoy it as wild land … but as land becomes more valuable for building it is inevitable that private owners will assert their rights…” He goes on to say that “as sure as the tide rises and falls, Dogtown will eventually be ‘improved’ and ‘developed’ for industry, an airport, or private homes, and we will all lose out forever.”

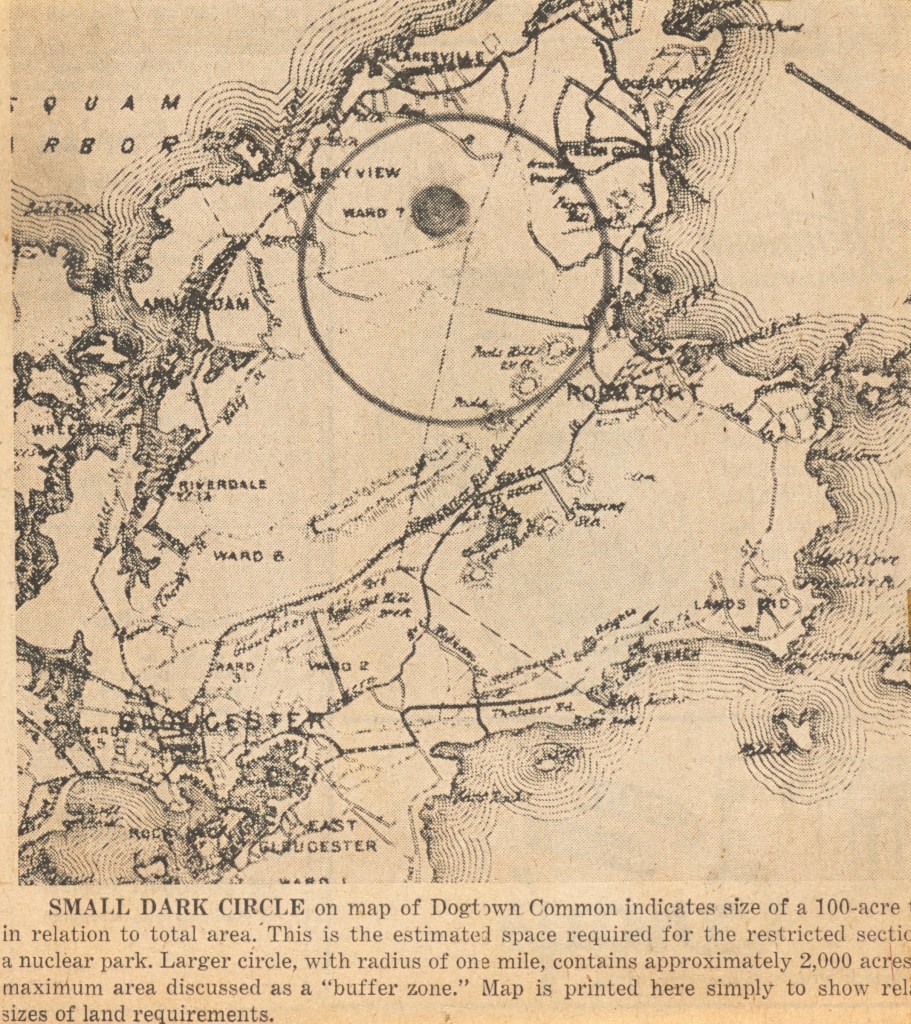

This was not idle speculation. In 1944, a private airport was proposed near Whale’s Jaw. Early in 1958, a group known as the Gloucester Industrial Development Commission proposed that a State Atomic Energy Service and Manufacturing Park be constructed in Dogtown. In December 1958, the state opted for a site on Cape Cod instead. Had it been otherwise, the City would have taken by eminent domain 2000 acres in Dogtown for the atomic park and surrounding buffer zone. In 1967, the Department of Defense considered an area around Briar Swamp as a possible site of a radar system for the Sentinel anti-ballistic missile system. More recently wind farms and other development projects have been proposed for Dogtown.

Public opinion was split on the Dogtown Reservation. In the summer of 1959, the Dogtown Foundation and a group known as the Dogtown Land Grab Opponents presented their views. In an article in the GDT (7/15/59), Paul Kenyon writes the “Opponents” stated: “People can enjoy Dogtown now. Nobody stops people from hunting, bird watching, berry picking, etc. The owners are generous enough to let the people use the land. Why spend tax money to get advantages that we already have?” The response by the Dogtown Foundation was: “The trustees feel that if the question drifts along, Dogtown will not continue forever as it is. We feel that the best way to preserve it for the people is for the city to take the land as soon as the legal steps have been taken.” Other concerns voiced at the meeting are discussed in Kenyon’s two subsequent articles (GDT 7/16-17/59).

Ultimately, the objective of acquiring the land and leasing it to Dogtown Foundation for conservation, restoration, and protection was never achieved, at least, not directly. Following the construction of the Babson Reservoir in 1930, city engineers looked in Dogtown for places to build another reservoir. Initially, the City surveyed an area in Dogtown along Wine Brook south of Briar Swamp. A few years later, the City decided to take the parcels originally slated for the Dogtown Reservation for the construction of a new reservoir, which was built in a valley at the end of Gee Avenue flooding a section of the old Commons Road.

Developing a Management Plan for Dogtown

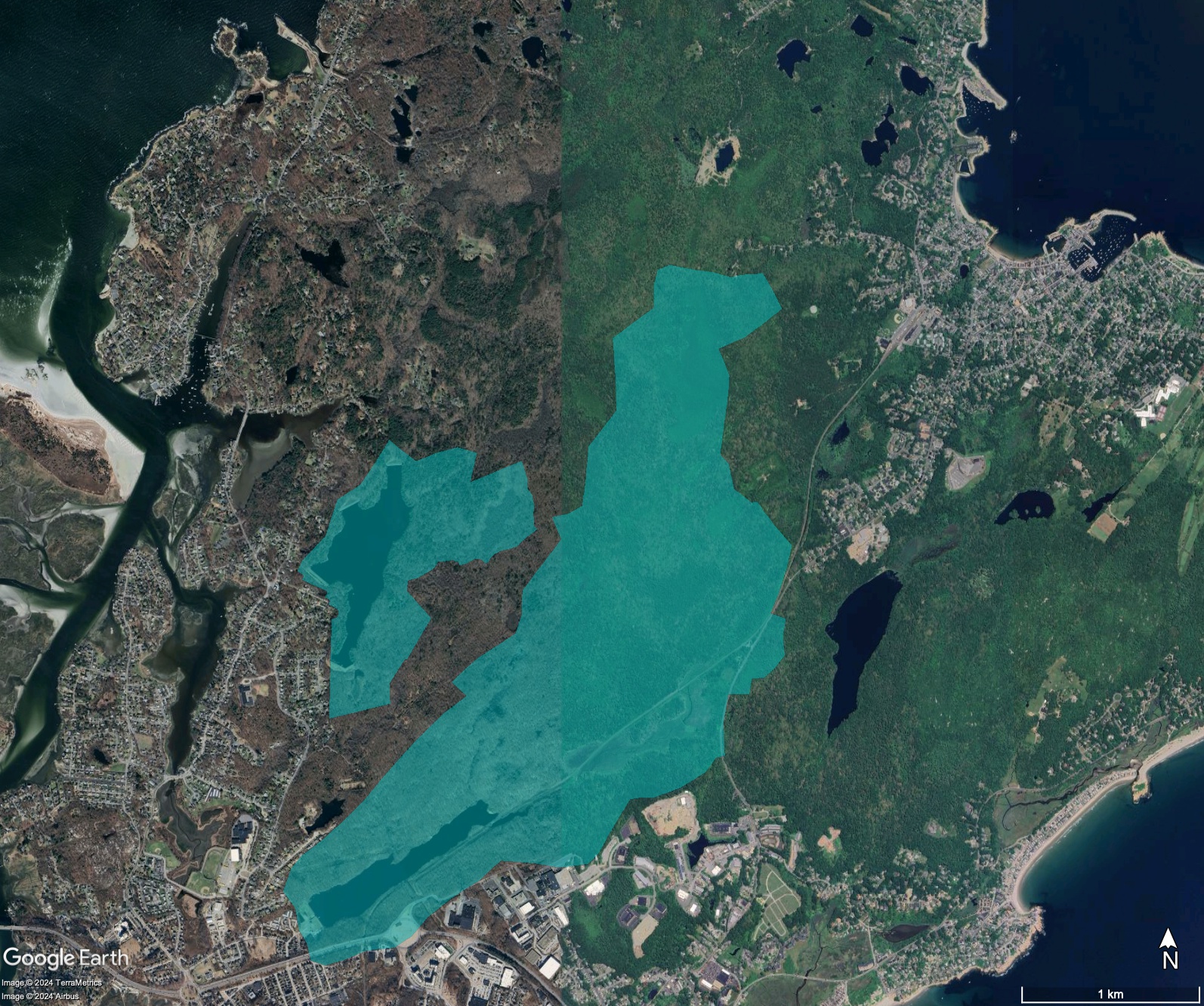

Together with the Babson Reservoir and its watershed, the Goose Cove Reservoir and watershed cover much of Dogtown, and are therefore protected under the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act. But what about the rest?

Twenty years later, the question of what to do about Dogtown came up again. In the summer of 1985, a group known as the Dogtown Steering Committee submitted a report to the Mayor entitled: Developing a Management Plan for Dogtown. The committee made a number of recommendations that considered both the threat of development and the lack of management. The greatest threat of development was along Dogtown Road.

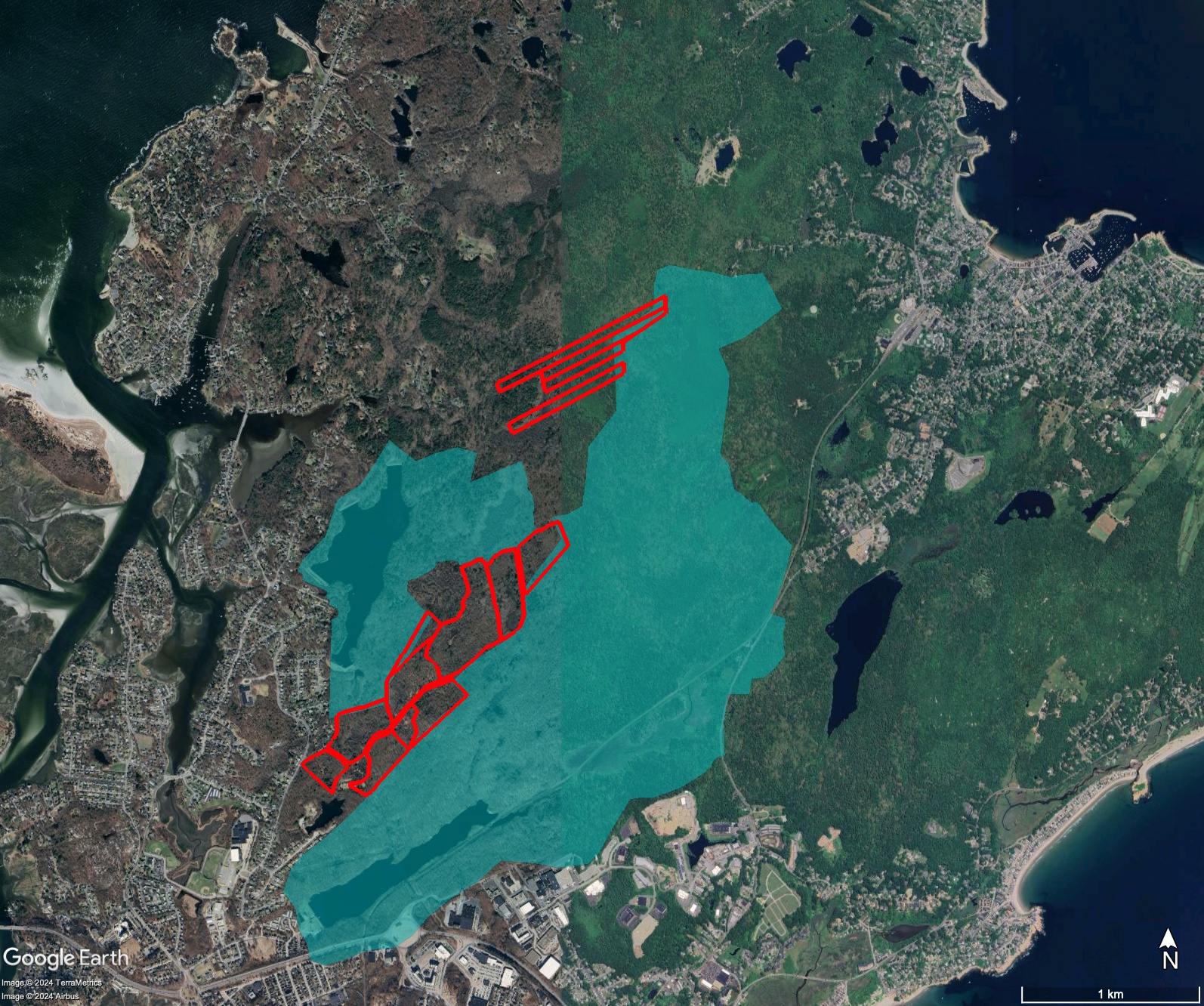

To avert the threat of development, the working group proposed that the City purchase critically situated land with the aid of a Self-Help grant from the state, and that the Greenbelt Association raise privately the funds needed for the City’s share. During the year that followed, the Conservation Commission, aided by the working group, applied for and was awarded a Self-Help grant amounting eventually to $266,000. In June, 1985, the Greenbelt began its campaign to raise the City’s share, or $66,000 (20% of the appraised value of the 135 acres), plus funds already expended by Greenbelt and Massachusetts Audubon for appraisals and title searches. Meanwhile, the City Council voted to take the land by eminent domain, both to clear some cloudy titles and to bring to a head a series of inconclusive negotiations with one set of professed owners. While the latter may yet challenge the price being paid, the best opinion is that such a challenge will fail. In any event, the land is now safe, and thus far at no cost to the City.

As described in a previous article, the land paid for by the state’s Self-Help grant was later given Article 97 protection.

Some but not all of the recommendations of the Dogtown Steering Committee were enacted. Eventually, the Dogtown Steering Committee became the Dogtown Advisory Committee, an ad hoc committee, with no real authority reporting directly to the Mayor. Besides developing and distributing a trail map, and working with private groups like Essex County Greenbelt, Cape Ann Trail Stewards, Friends of Dogtown, and others, little progress was made on questions of land use, specifically the “temporary” use of one of the parcels as a compost area for the past forty plus years. In 2021, the Dogtown Advisory Committee became the Dogtown Preservation Commission, which was ultimately absorbed into the Open Space and Recreation Committee in 2024.

Current Impasse

Article 97 conserves open space but does not protect specific parcels from development.

The PARTICIPANT [the City of Gloucester] acknowledges Article 97 of the Massachusetts Constitution which states in part that: ‘Lands and easements taken or acquired for such purposes shall not be used for other purposes or otherwise disposed of except by laws enacted by a two thirds vote, taken by yeas and nays, of each branch of the general court.’ The PARTICIPANT hereby agrees that any property or facilities comprising the PROJECT will not be used for purposes other than those stipulated herein or otherwise disposed of, unless the PARTICIPANT receives the appropriate authorization for the General Court, the approval of the Secretary of Environmental Affairs, and any authorization required under provisions of Mass. G.L. c. 41, s. 15A.

At first glance, this would seem to provide some level of protection for these parcels until we go on to read the next paragraph:

The PARTICIPANT further agrees that despite any such authorization nd approval, in the event that the property or facilitates comprising the PROJECT are used for purposes other than those described herein, the PARTICIPANT shall provide other property and facilities of equal value and utility to be available to the general public for conservation and recreational purposes provided the equal value and utility and the proposed use of said property and facilities is specifically agreed to by the Secretary of Environmental Affairs.

It is not impossible to imagine a scenario in which the City might one day decide to develop this land effectively splitting Dogtown in two. Nothing under Article 97 would prevent that from happening.

A conservation restriction (CR) allows for more flexibility in defining the specific uses and restrictions that apply to specific parcels of land. The restriction is legally enforceable by a third party (like a land trust or conservation organization), which adds an extra layer of oversight beyond the municipality or government agency that owns the land. So why not combine the protection of Article 97 with the customization and oversight offered by a CR?

One of the objections given by the 1950s Dogtown Land Grab Opponents was that under the terms of the agreement to lease land to the Dogtown Foundation, “the city would lose all control or right to regulate the use of said land.” A similar sentiment was expressed during the 2019 public hearings regarding the proposed nomination of Dogtown for the National Register of Historic Places.

If we allow a third party in to ensure Dogtown’s protection then we must play by their rules. For example, here are some rules and regulations for Essex County Greenbelt properties:

- Hours: Use the property between sunrise and sunset.

- Clean up: Clean up after your dog.

- Permissions: Contact the Greenbelt office for permission to do other activities.

- Hunting: Only Greenbelt members can get hunting permits, which are issued annually. Hunters must have their permit with them at all times.

- Farming: Greenbelt farmland is usually rented to local farmers on a 5-year basis. Farmers may be allowed to develop some infrastructure.

- Property monitoring: Volunteers are asked to report to the Greenbelt at least four times a year. Volunteers should have basic trail maintenance knowledge and be in good physical health.

- The Greenbelt’s Land Stewardship staff maintains the properties, including creating and maintaining trails, mowing fields, and installing signage and fencing.

It is highly unlikely that those who opposed the National Register nomination would be willing to accept all of these rules.

The only alternative then is that we must trust the City – our elected officials and individuals who serve on Open Space and other relevant commissions – to ensure the Article 97 parcels along Dogtown Road are never swapped out for other open spaces and are never developed. After all, in the words of Thomas Jefferson, “The government you elect is the government you deserve.”

Feature photo from the 1930s of the site where Marsden Hartley painted “Summer, Outward Bound” from the Cape Ann Museum’s Dogtown photo collection. (Courtesy CAM/Monica Lawton)

Leave a comment